Why is it so hard to hear in background noise? Even people with normal hearing struggle to hear well when there is competing noise. Add a hearing loss to the mix, and you have one of the most reported difficulties of those with hearing impairment…”I can’t hear in background noise!”

image via

The physics of sound and human anatomy has everything to do with this complaint.

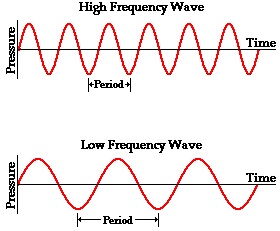

Some speech sounds that give meaning to words have high frequency energy (or high pitch energy). The /s/ sound, which appears most frequently in English is high frequency. Other examples are /f/, /th/ and /k/. Each of these sounds or phonemes happen in or above 4000 Hz. Unfortunately, the high frequency range is not where our ear is sensitive to loudness. I can turn up a sound twice as loud in high frequencies and show the loudness on a sound level meter is doubled, but it will only sound a little louder to the person listening.

image via

In contrast, lower frequencies (or low pitches) are where humans detect loudness most discreetly. I can do the same experiment with low frequencies, and most folks will be able to easily detect even small changes in loudness, and double loudness is obvious.

Think about how easy it is to hear someone’s loud bass sounds even a couple cars away, or even in your house a few rooms away. The wavelength of these bass sounds are long and very robust. Low frequency sound wavelengths are long enough to move around corners and through walls.

High frequency sounds are the opposite. The wavelengths are short and rather fragile. They won’t get through walls at all, but dissipate when they encounter obstacles.

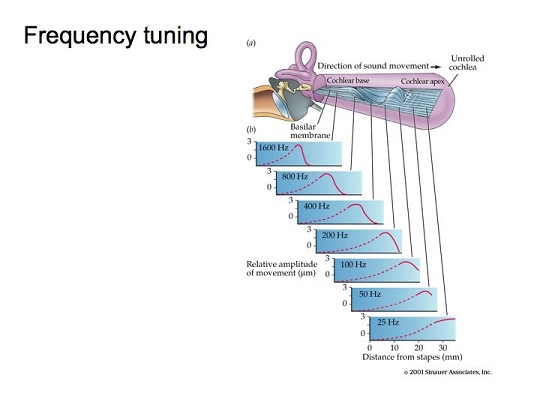

Why does this make a difference? Most noises are low and mid frequency sounds. The energy in the low frequencies is strong, and due to a phenomenon called “the upward spread of masking”, these strong low and mid frequency sounds smear forward and cover up the high frequency sounds. This masking effect is also due to human anatomy. Inside the snail-shaped cochlea or inner ear, humans detect the high frequencies at the entrance to the inner ear. The lower pitches are at the end.

image via

The low frequencies literally spread through the entire length of the inner ear, thus literally covering up some high frequencies at the same time.

Think about how hard it is to hear someone talk to you when the faucet is running, or if there is music in the background. How much more difficult is it to hear when you are dining at a busy restaurant?

image via

Now imagine that you already struggle to hear those high pitches (one of the most common forms of hearing loss). Add in that competing noise, and you can see how frustrating this is for folks with hearing loss!

The good news is that there are many things to do that can help with hearing in noise. First, make sure you can see the person you want to communicate with. Sixty percent of communication is non-verbal. We learn a lot about meaning by observing our communication partner. Second, put your back to the noise. Our brains are really good at focusing on what is most important, and placing the noise behind us is a great tool to maximize our brain sorting out that noise. Third, rephrase what you did hear. If you missed something, let your partner know what you did hear…much better than just saying “huh?” or worse, pretending you did understand.

What about those with hearing loss? Modern hearing technology employs some great tools to help. One of the most helpful are directional microphones. You may have seen this employed in noise-cancelling ear phones. This technique is one of the best tools we have. Another is noise reduction algorithms which listen to the incoming speech signal, and actually sort out speech from noise. This works best when the noise is not additional speakers, but clinking plates or machine noise.

We live in a noisy world which can interfere with communication, especially for those with hearing loss. However, there are some wonderful skills we can learn, and tools to use to make this less of a problem.

Additional reading:

Physics of pitch and frequency